For the Love of the Game: DistrictCon's Year 1 Junkyard

Notes from judging DistrictCon's Junkyard Year 1 — a Pwn2Own-style exploit contest targeting end-of-life devices. Disco balls, DNA sequencers, gym treadmills, and self-propagating game worms. Includes exploit chain diagrams for all eleven talks.

I spent this past weekend in DC judging the Junkyard at DistrictCon Year 1, and I'm still processing how good it was. If you're not familiar with the format: The Junkyard is a Pwn2Own-style exploit contest, but instead of going after the latest and greatest, researchers bring end-of-life targets — things that vendors have stopped supporting, that are still everywhere, and that nobody is looking at anymore. They present their research live, demo exploits on real hardware (or at least try to — more on that later), and compete for prizes across categories like most impactful, best meme target, and most engaging presentation.

Last year, the standout was someone who popped a traffic light controller they'd bought off eBay for $50 — the same make and model as the ones controlling the intersection right outside our hotel. That one stuck with me. I ended up referencing it in a piece for SC Media about the Netflix Zero Day series, because it was such a perfect illustration of how fragile our critical infrastructure actually is when you start looking at the EOL attack surface.

This year was even better. The diversity of targets, techniques, and the sheer creativity of the researchers blew me away. Here's a rundown.

The Lineup

Eleven presentations across the day. The range of targets alone tells you something about the state of the EOL problem: IoT power strips, routers, a 2003-era video game, a DNA sequencer, the Linux kernel, a C2 framework used by nation-state actors, a classic '90s PC game, a gym treadmill, ARM GPU kernel drivers, industrial barcode scanners, and Windows 7's kernel.

Some of these were just funny. Some were pretty sobering. Most were a blend of both.

Standouts and Themes

The Fun Factor

One of the things that makes the Junkyard work is the emphasis on hacking for the sake of hacking. These aren't corporate engagements with scoping documents and rules of engagement — they're researchers picking targets because they're curious, because something caught their eye, because they thought it'd be kinda fun.

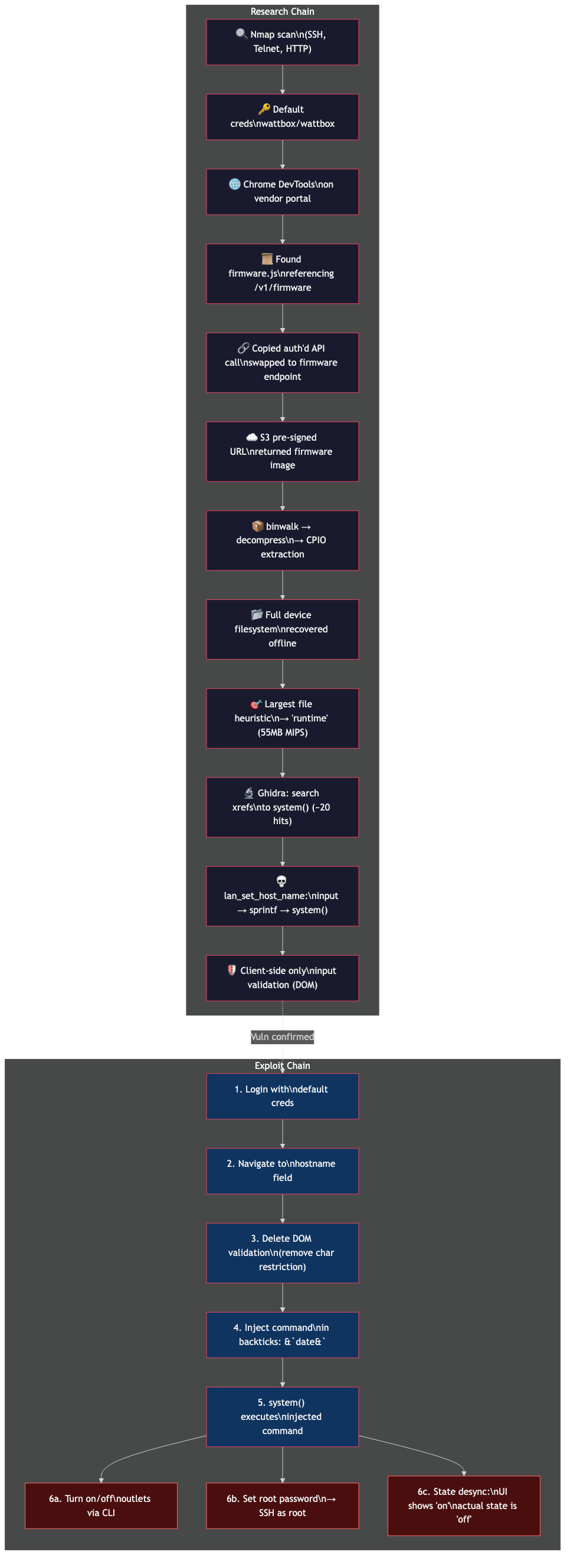

noperator kicked things off with WATT IS LOVE, popping a WattBox — a networked surge protector with a web interface. The chain was clean: default creds, hidden firmware API endpoint found by digging through the vendor's frontend JS, Ghidra to find a classic command injection path, and then a live demo that turned on a disco ball and speaker system from the audience. The kicker was demonstrating that you could turn off outlets via the command line while the web UI still showed them as "on." For a device designed to remotely manage power in server racks, that's a scary state desync.

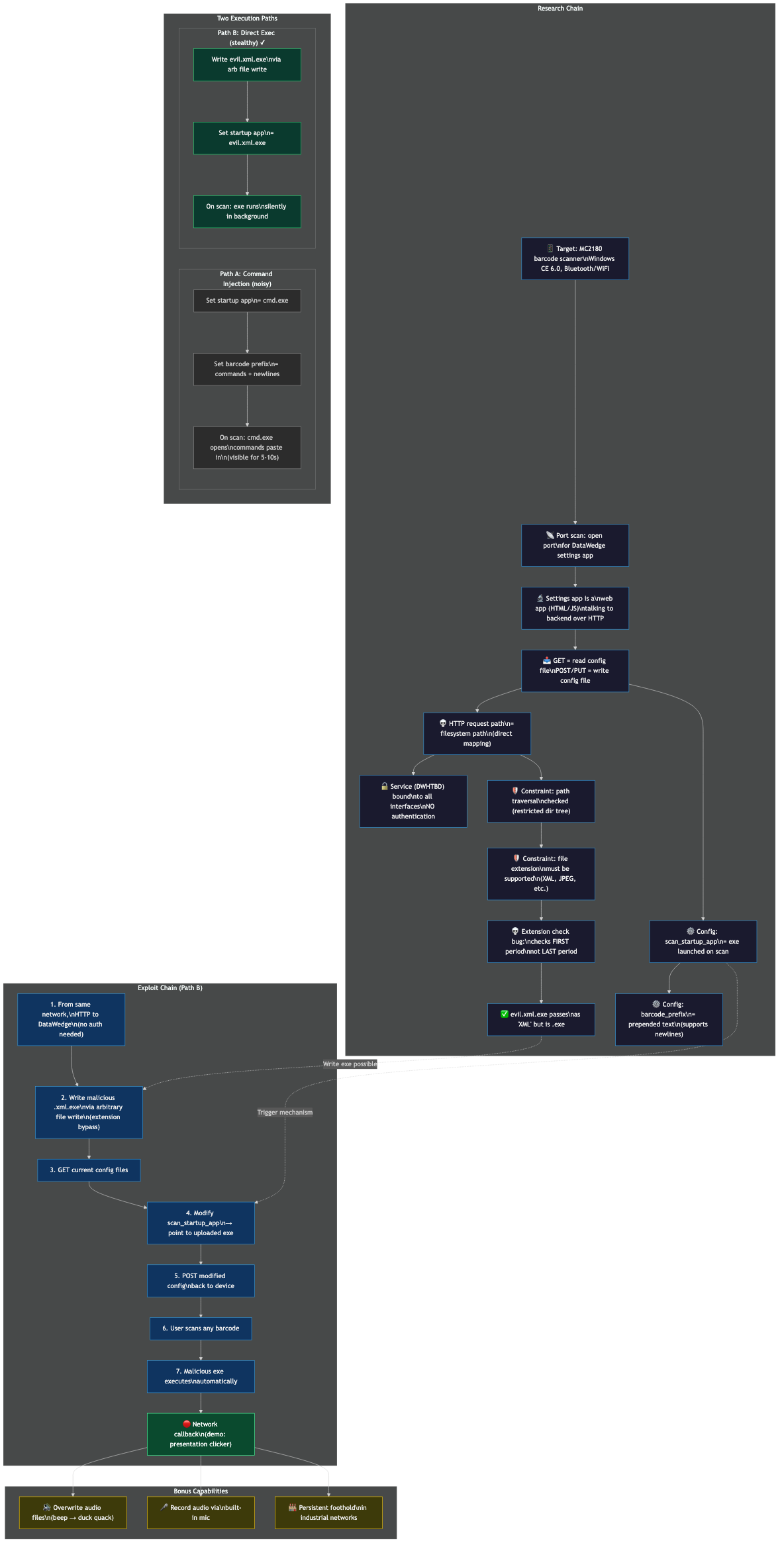

zaratec turned her barcode scanners into a presentation clicker in Quacking Between the Lines. She exploited a Zebra MC2180 running Windows CE by finding that the "settings app" was actually a web service bound to all interfaces with no auth, and then chained an arbitrary file write (with a file extension check that only validated the first period — so evil.xml.exe passed as XML) with a configuration abuse that made her malicious executable fire every time someone scanned a barcode. She then used that as her slide advancer for the entire talk, which is probably the most confident flex of exploit reliability I've ever seen on a stage.

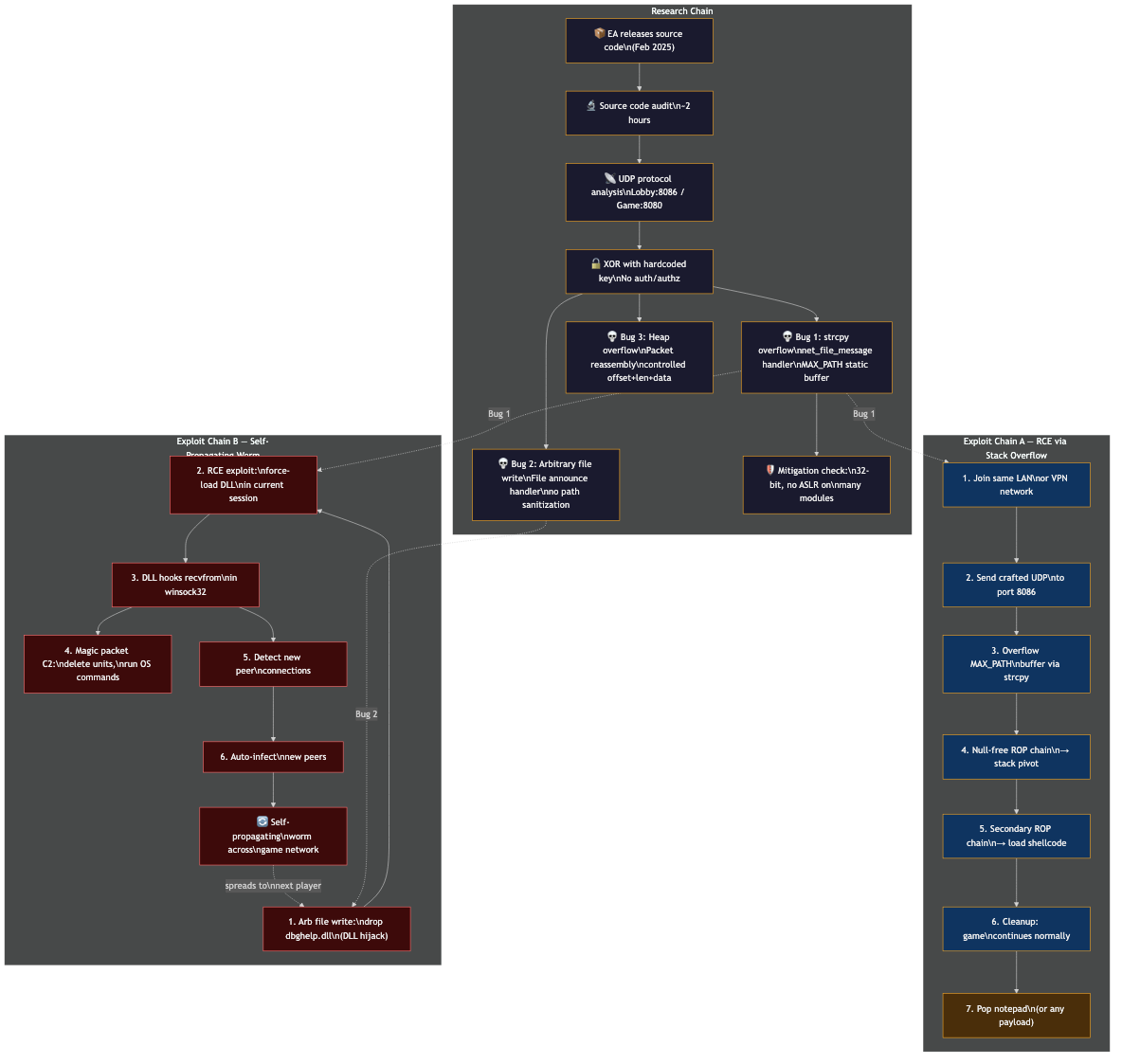

jordan9001 and drone found three bugs in about two hours of reading the source code EA released last year in General Graboids, turned one into a fully working RCE, and then — because apparently that wasn't enough — built a self-propagating worm that spreads between players via the game's peer-to-peer network. They used an arbitrary file write to drop a malicious DLL that gets loaded on startup (classic DLL search order hijacking), hooked the network recv APIs for a C2 channel, and could delete all your buildings while you were playing. The community that still maintains the game actually worked with them to get patches out, which is a great example of responsible disclosure working outside the traditional vendor model.

The Scary Factor

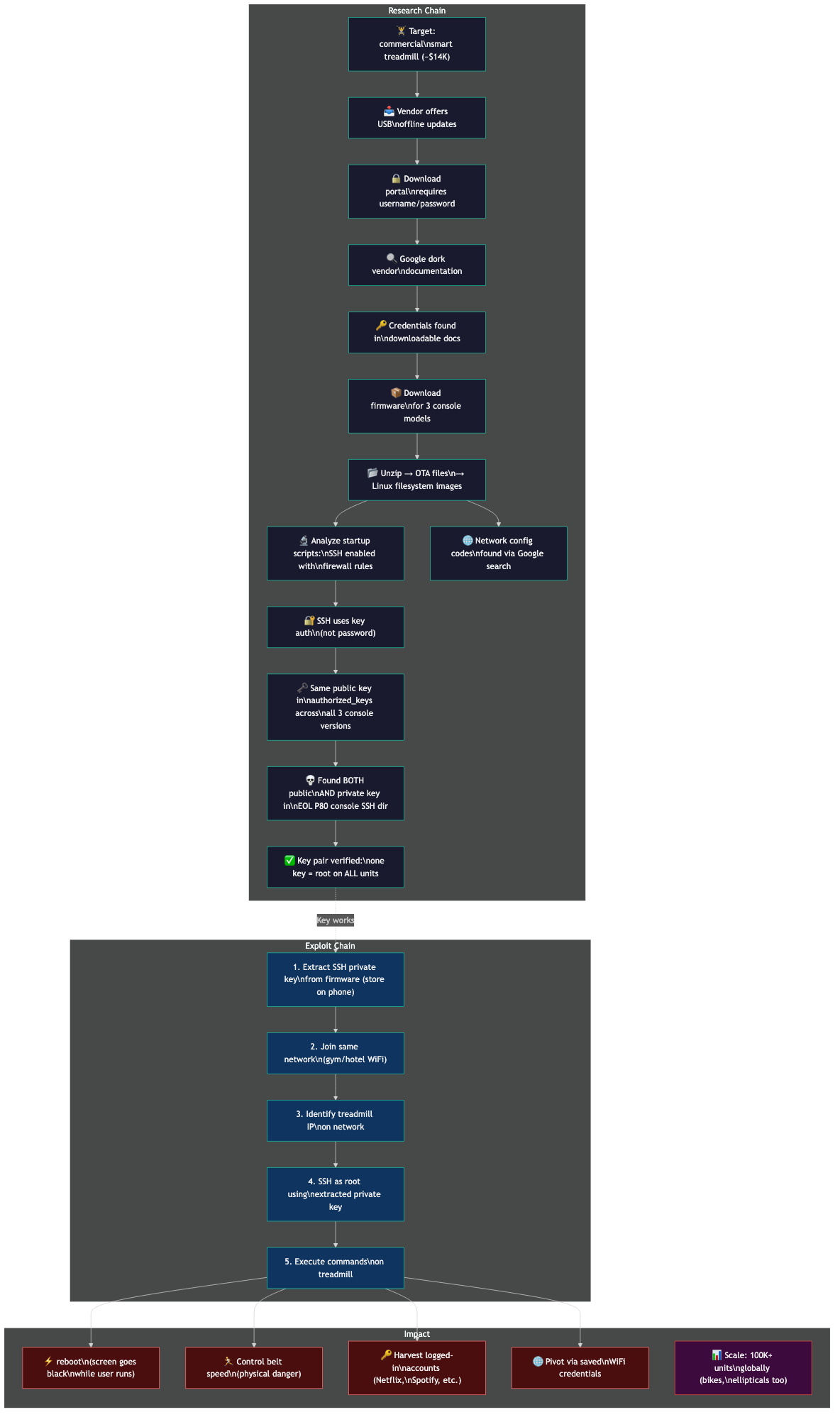

imthreevil and qu3ri brought Flex Force — a treadmill hack. Well, they brought the hack — they couldn't bring the actual treadmill because they cost $14,000. Instead, they used the one in the hotel gym. The chain was delightfully awful: Google-dorked the vendor documentation to get the firmware download portal credentials, extracted OTA update packages, found that every single unit of this brand shares the same SSH private key (included in the EOL console's firmware image), and then SSHed into the treadmill from a phone. They rebooted it live while someone was running on it. One key. Every treadmill this vendor has ever shipped. Tens of thousands of devices.

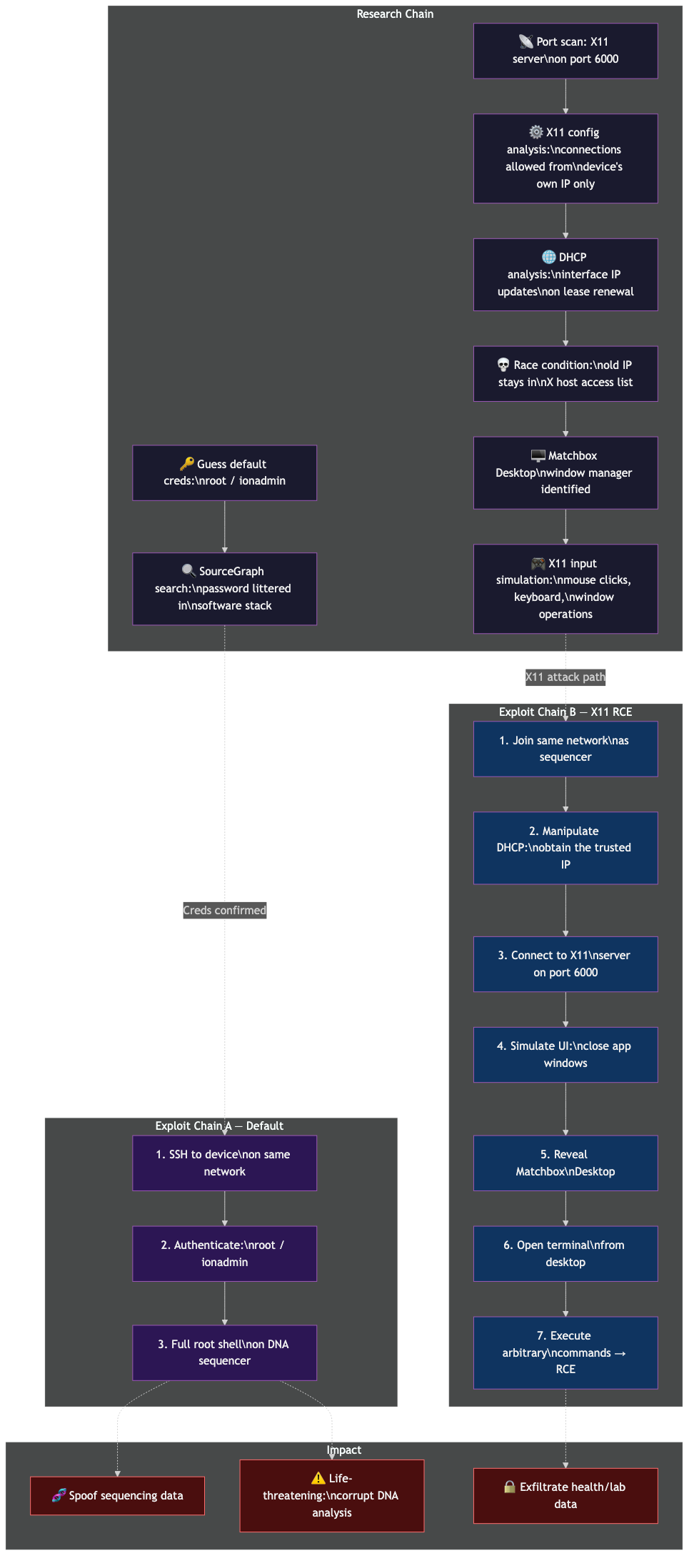

0xhadd0ck and ex0dus brought Twisted Ladder — a Thermo Fisher Ion OneTouch 2, a DNA sequencer used in medical labs. Default creds of root/ionadmin (findable via SourceGraph), plus an X11 server that could be hijacked via DHCP IP impersonation. These things are EOL since 2023, they're expensive, they're in labs processing health data, and the replacement cycle is glacial. It's the medical device problem in microcosm.

The Technical Depth

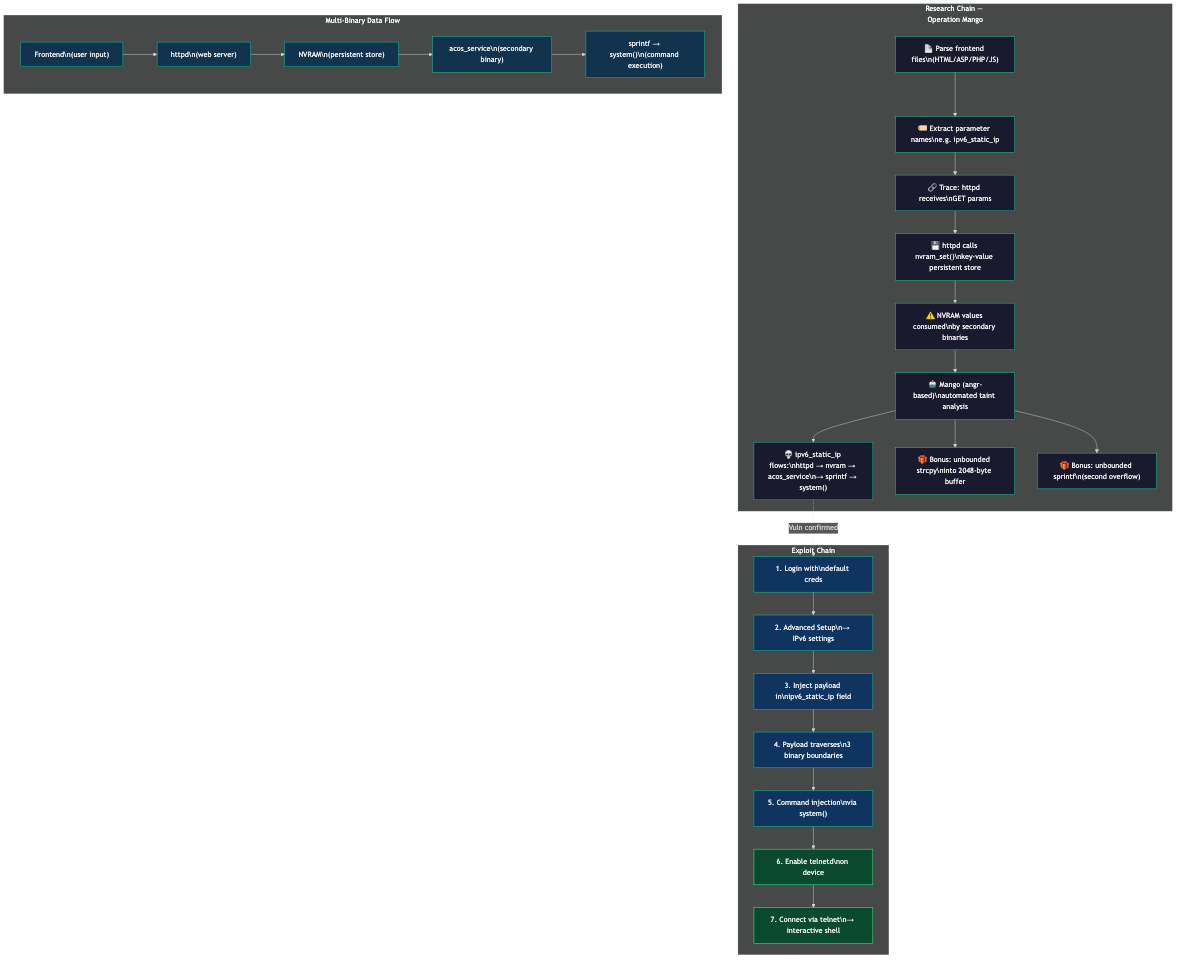

Wil Gibbs from ASU brought Route Box, targeting a NETGEAR AC1450 — an EOL office router. Rather than manual auditing, he used Mango, an automated static analysis tool built on the angr symbolic execution framework, to trace user input across multiple binary boundaries. The tool found a command injection path that crossed three binaries: httpd → NVRAM → acos_service → system(). Plus a couple of buffer overflows as a bonus.

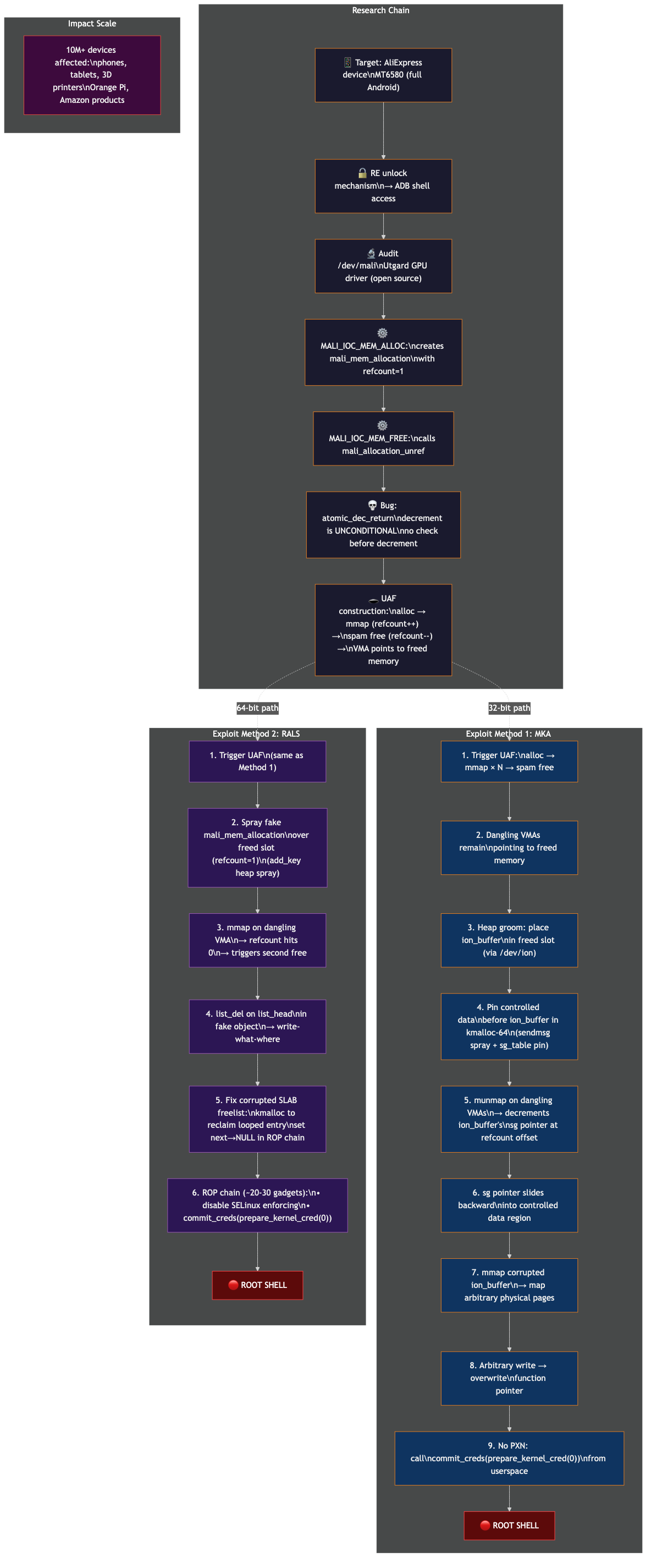

tnr went deep on an ARM Mali GPU kernel driver bug affecting MediaTek and Kirin chipsets in ARMageddon. He bought cheap AliExpress devices, found an unconditional refcount decrement in the free path, and developed two different exploitation methods for different hardware variants — one for 32-bit devices without PXN (using ion buffer corruption for arbitrary physical page mapping), and another for 64-bit with PXN and SELinux (using a ROP chain of ~20-30 gadgets that fixed the SLAB freelist corruption it caused along the way). Estimated impact: 10 million+ devices. The ARM response to his disclosure was to delete the open-source driver repository.

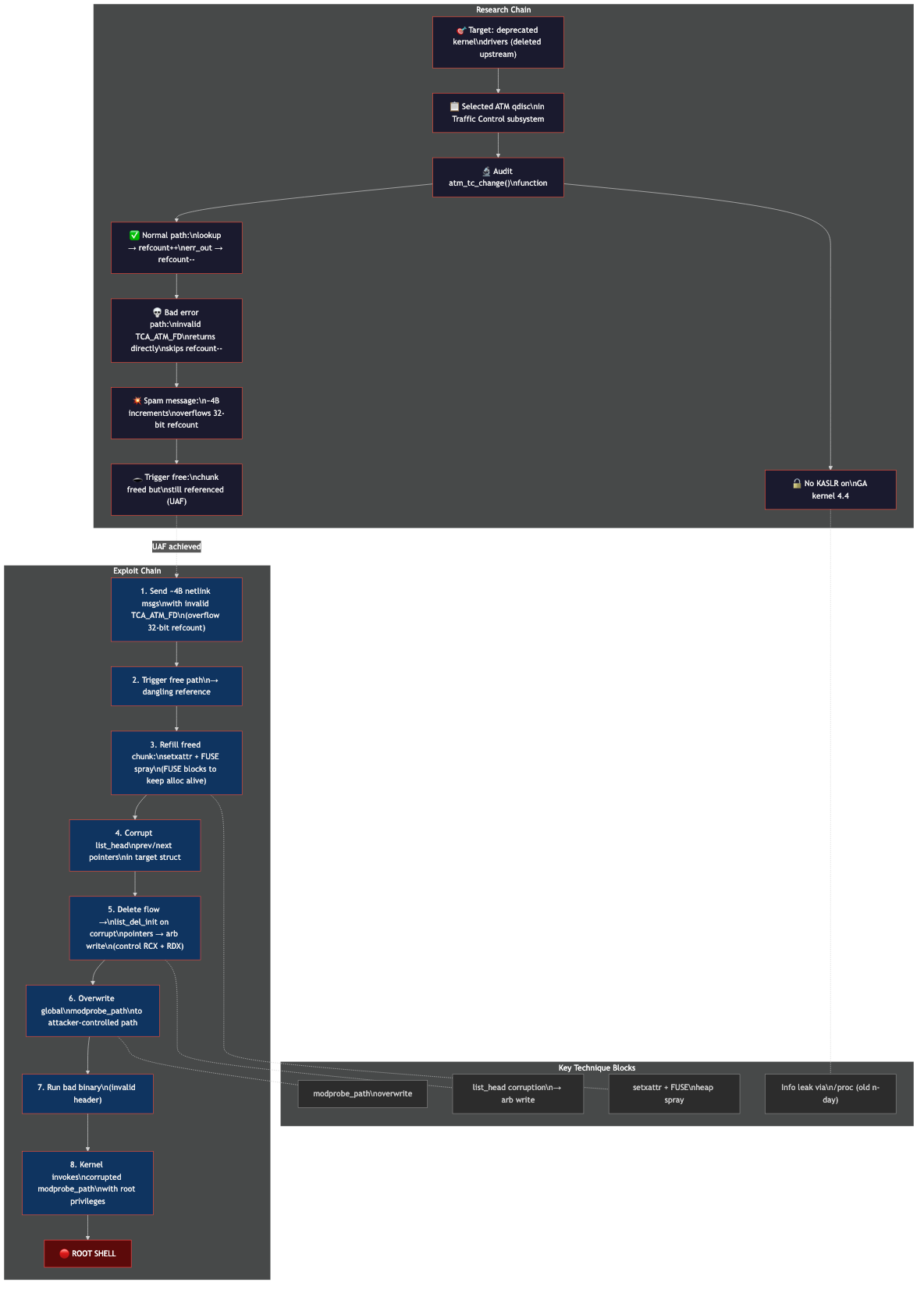

ex0dus's Counting Chaos exploited a refcount management bug in a deleted ATM traffic control driver on Ubuntu 16.04 — a 32-bit counter that had to be overflowed ~4 billion times before the real exploit could even start. The best case runtime was 20 minutes. The technique chain — setxattr+FUSE heap spray, list_head corruption for arbitrary write, modprobe_path overwrite — was textbook kernel exploitation, and the writeup in the Junkyard edition of Phrack magazine is worth reading.

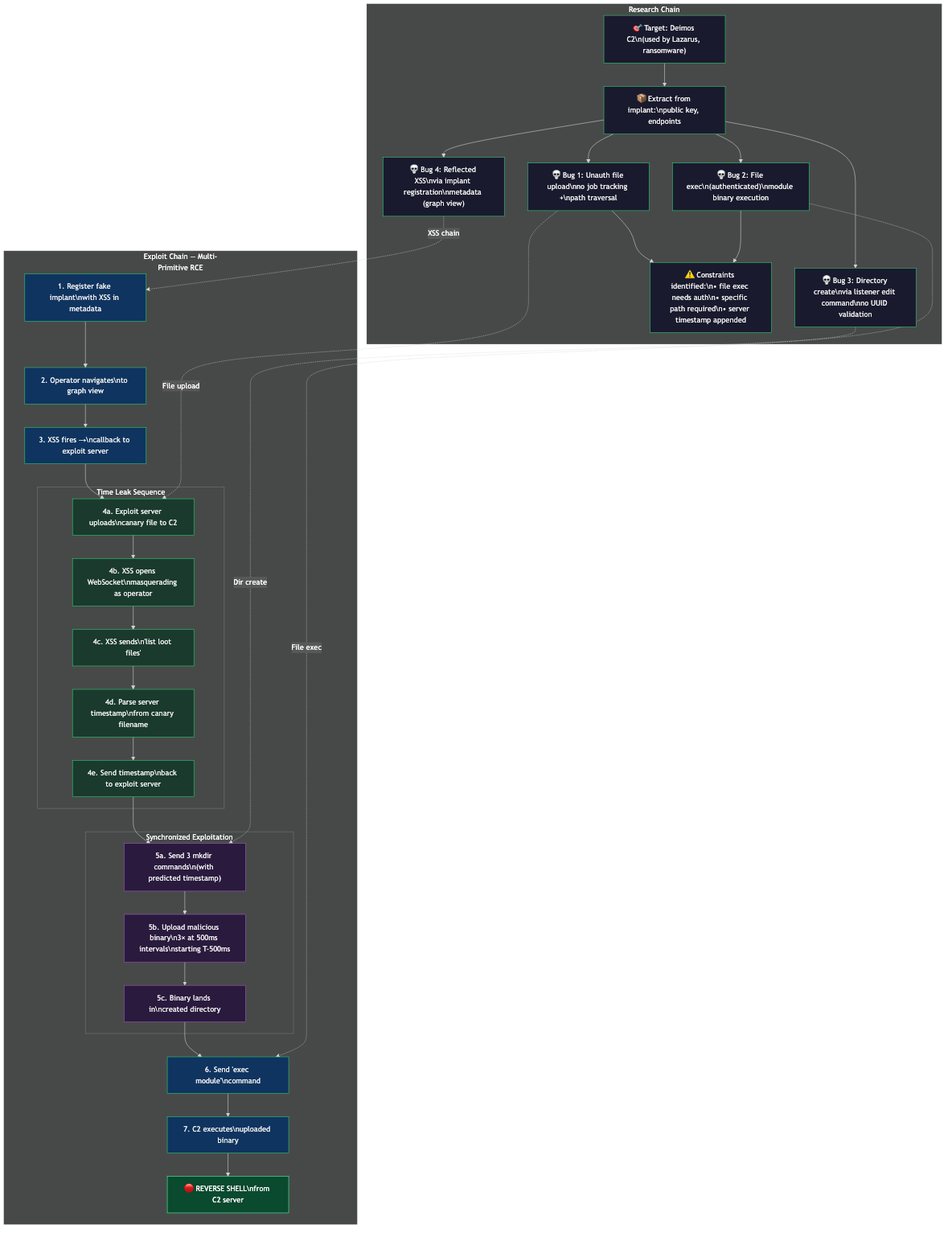

gnomesec hacked the hackers in H2C2, targeting the Deimos C2 framework — the same one attributed to Lazarus Group and various ransomware operators. The challenge was that his initial bug primitives were constrained in frustrating ways: an authenticated file exec, timestamps appended to every upload, and a directory structure that was hard to control. He chained an XSS in the registration metadata with a time-leak via canary file uploads, WebSocket auth bypass, and millisecond-precision synchronized file placement to land a binary in exactly the right path at exactly the right time. The whole thing was documented in Phrack. When asked what kept him going through the constraint hell, his answer was perfect: "Peer pressure. I'd already told people I found the bug."

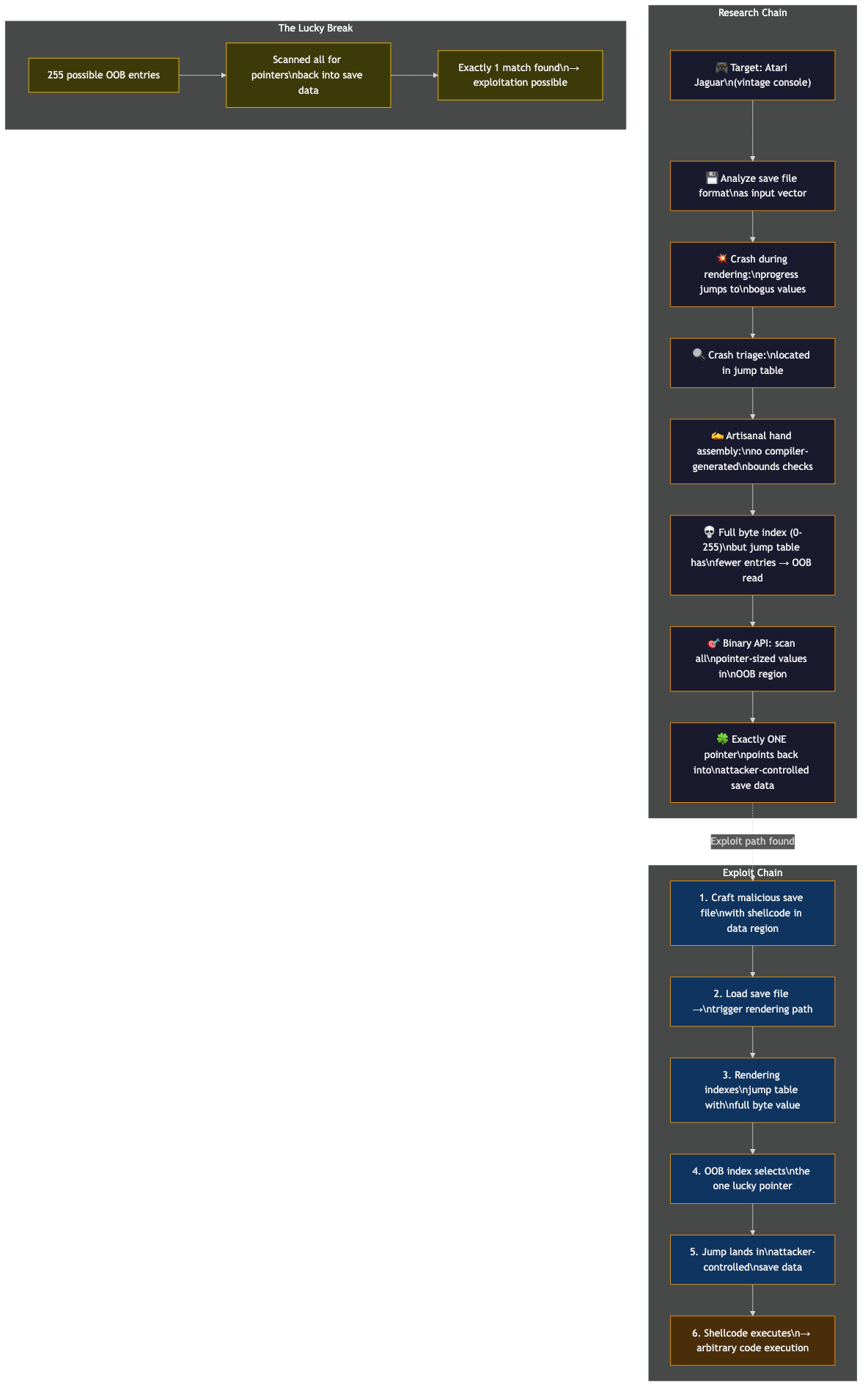

rdjgr and arcticx brought RCECoaster — targeting RollerCoaster Tycoon, the classic 1999 PC game famously hand-written in x86 assembly by Chris Sawyer. They reverse-engineered the custom save file format, found an out-of-bounds jump table read in the save file renderer (no bounds check because it was hand-written assembly, not compiler-generated), scanned 255 potential OOB entries for pointers back into attacker-controlled data, found exactly one, and used it to redirect execution into shellcode embedded in the save file. Sometimes exploitation comes down to one lucky pointer.

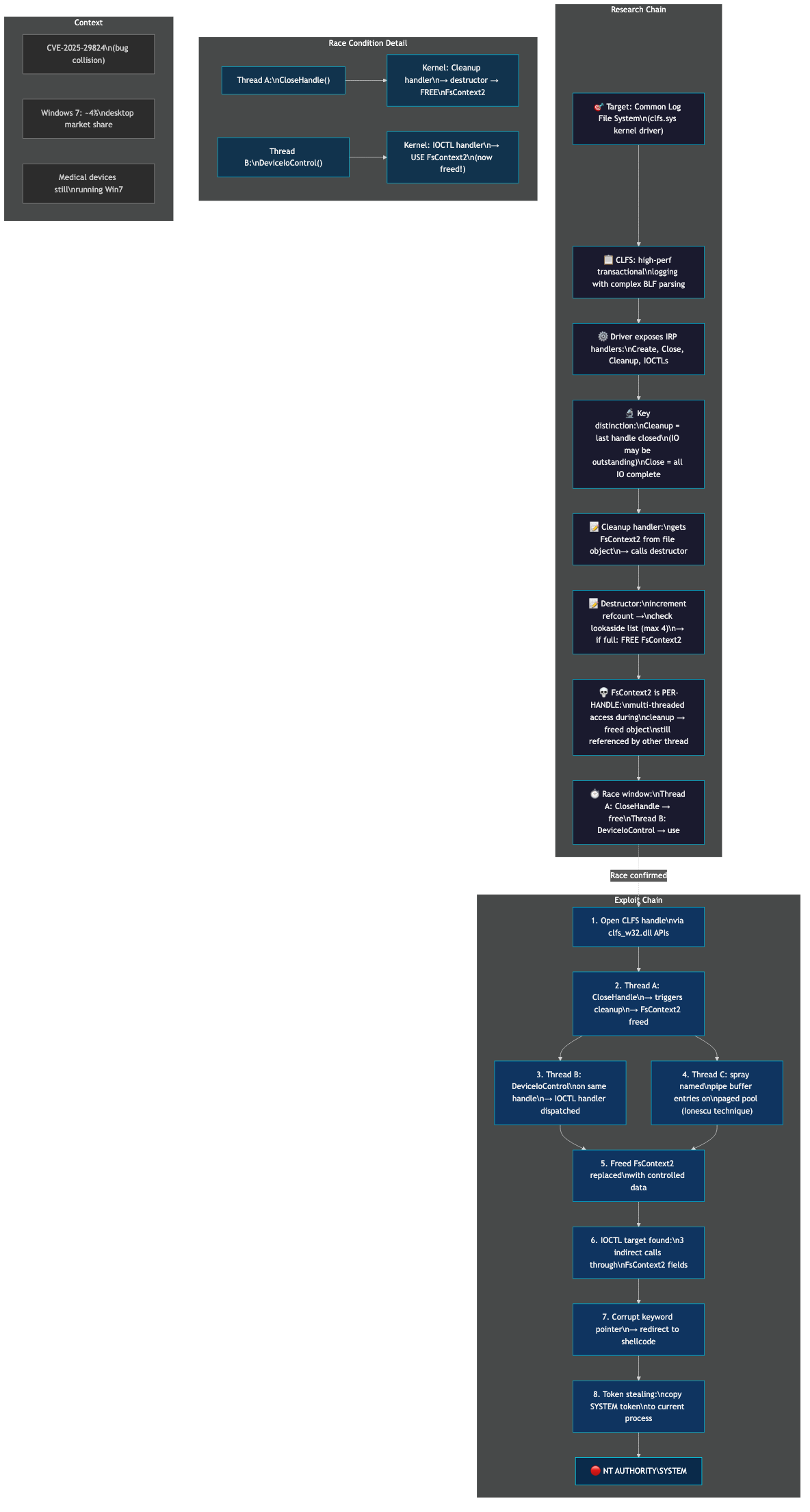

And 0xhadd0ck's Lucky Seven — a Windows 7 CLFS kernel driver LPE that collided with CVE-2025-29824 — demonstrated a race condition between the cleanup and close IRP handlers that gave a use-after-free on a per-handle structure, exploited via named pipe spray on the paged pool. Windows 7 still runs on ~4% of desktops. A lot of those are medical devices.

The Live Demo Gods

I have to mention the live demos, because they're a core part of what makes the Junkyard special and also what makes it terrifying for the presenters. Wil Gibbs from ASU had a NETGEAR router that needed a full reboot cycle mid-demo. 0xhadd0ck and ex0dus had their Ion OneTouch 2 exploit fail to connect on stage. Several others had last-minute issues. This happens every year and it's part of the charm — these are real devices running real exploits in a real conference environment, and anyone who's done this knows that the demo gods are fickle.

Mapping the Attack Chains

After the event, I sat down with the full transcript of all eleven presentations and worked through each one with Claude to decompose the research methodologies and exploit chains into structured, step-by-step breakdowns. The flow diagrams you see throughout this post are the result.

The process itself was interesting. Each presentation followed a natural two-phase pattern: the research chain (how the researcher found the vulnerability) and the exploit chain (how they turned it into a working exploit). Mapping these out makes a few things visible that are easy to miss when you're watching talks in real time:

The techniques repeat. Default credential testing shows up in four of the eleven talks. Refcount management bugs appear in three. Arbitrary file write primitives appear in three completely different contexts (a video game, a C2 framework, and a barcode scanner). When you break exploit development into reusable "blocks," patterns emerge across targets that look nothing alike on the surface.

The creativity is in the chaining. Any individual technique in these talks — a heap spray, a DLL hijack, a path traversal — is well-documented. What makes these exploits work is the way researchers combined constrained primitives into working chains. gnomesec's Deimos C2 exploit is the clearest example: four separate bugs, none sufficient alone, chained with millisecond-precision timing into a full RCE. But you see it everywhere — the RCECoaster team scanning 255 OOB entries to find the one pointer that lands in their data, the Mali GPU researcher developing two entirely different exploitation strategies for different hardware variants of the same bug.

The constraints drive the innovation. The most technically impressive exploits weren't the ones with the easiest paths — they were the ones where the researchers had to work around frustrating limitations. A 32-bit refcount that takes 20 minutes to overflow. A file extension check that requires a double-extension bypass. A time synchronization problem that requires leaking the server clock via XSS. The constraints forced creative solutions that are arguably more interesting than the vulnerabilities themselves.

The full research and exploit chain analysis for all eleven talks — including a cross-reference index of reusable technique blocks — is available as a companion document. If you teach or study vulnerability research methodology, it might be a useful reference.

Why This Matters

There's a version of this post where I lay out the policy implications — and they're real. 83% of medical imaging devices run EOL operating systems. The FDA updated its guidance in 2025 specifically because of this. The ARPA-H program is funding automated vulnerability discovery and remediation for medical device firmware. These are known problems.

But I think the more important takeaway from the Junkyard is cultural. The security research community at its best is driven by curiosity, by the joy of figuring out how things work (and how they break), and by a sense of responsibility to share what they find. Every single team in this competition went through responsible disclosure before they were allowed to present. Several worked directly with user communities to get patches out when vendors wouldn't act.

That combination — the technical craft, the creativity, the responsible approach, and the sheer fun of it — is what this community looks like when it's healthy. It's what drew most of us to this field in the first place, and events like the Junkyard are a reminder that it's worth protecting.

Massive props to Mark Griffin and the DistrictCon team for building something that brings this out in people. I'm psyched for Year 2!