The Original Bug Bounty: Alfred Hobbs and the Great Lock Controversy of 1851

Alfred Hobbs: The OG bug bounty hunter who cracked England’s ‘unpick-able’ locks. His breaker mindset exposed flaws, sparked innovation, and proved no system is perfect.

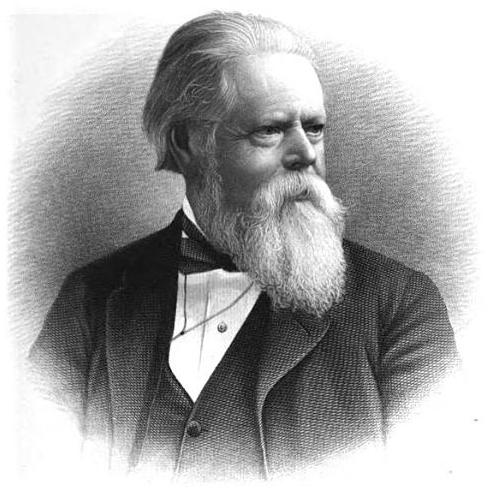

There's a recurring theme in the world of security, whether physical or digital: the assumption of invulnerability. It’s a dangerous mindset, one that history has repeatedly shown to be flawed. One of the most fascinating examples of this comes from the mid-19th century, when Alfred Charles Hobbs, an American locksmith, shocked Victorian England by exposing the vulnerabilities of what was then considered the world’s strongest lock. Hobbs’ story is not just a tale of technical ingenuity, it’s a case study in the importance of challenging assumptions and embracing the breaker mindset—a mindset that continues to drive innovation in security today.

The Context: Victorian England and the "Unbreakable" Lock

The mid-1800s was a time of rapid industrial and technological advancement. The Great Exhibition of 1851, held at the Crystal Palace in London, was a showcase of the era’s most impressive innovations. Among the many marvels on display was the "unpickable" lock designed by Joseph Bramah, a British inventor and locksmith. Bramah’s lock was a masterpiece of engineering, featuring a cylindrical key and a complex mechanism that was thought to be impervious to tampering.

For decades, the Bramah lock had been a symbol of security and ingenuity. It was so highly regarded that the company offered a reward of 200 guineas (equivalent to tens of thousands of dollars today) to anyone who could pick it. The challenge had gone unmet for over 60 years, reinforcing the lock’s reputation as unbreakable.

Enter Alfred Hobbs, a relatively unknown locksmith from the United States. Hobbs had come to England as a representative of the New York-based Day & Newell, a company that manufactured locks and safes. Unlike Bramah, who was a celebrated figure in British engineering, Hobbs was an outsider—a fact that would make his eventual triumph all the more shocking.

The Breaker Mindset: Hobbs’ Approach to the Challenge

Hobbs was not just a skilled locksmith, he was a thinker, a tinkerer, and, in many ways, a hacker in the truest sense of the word. He approached the Bramah lock not with reverence but with curiosity and skepticism. He understood that no system is perfect and that every design, no matter how ingenious, has its flaws.

Hobbs’ method was methodical. He studied the lock’s mechanism, identified its assumptions, and tested those assumptions to find weaknesses. This is the essence of the breaker mindset—a mindset I’ve often described as “understanding where the gaps are, what assumptions have been made, and what assumptions have been missed”. Hobbs didn’t just see the lock as a barrier, he saw it as a puzzle to be solved.

After 51 hours spread over 16 days, Hobbs succeeded in picking the Bramah lock. His achievement was a sensation, not just because he had done the seemingly impossible, but because of what it represented: the fallibility of even the most trusted systems.

The Fallout: Disruption and Innovation

Hobbs’ success was a wake-up call for the security industry of his time. It exposed the dangers of overconfidence and the need for continuous improvement. The Bramah lock, once thought to be unbreakable, was now just another flawed system in need of refinement.

But Hobbs didn’t stop there. He went on to challenge another iconic lock of the era: the Chubb detector lock. Like the Bramah lock, the Chubb lock was considered a pinnacle of security. It featured a mechanism that would disable the lock if tampered with, making it particularly challenging to pick. Hobbs, however, was undeterred. He demonstrated that the Chubb lock, too, could be defeated, further cementing his reputation as a master locksmith and a disruptor of the status quo.

The impact of Hobbs’ work was profound. It forced manufacturers to rethink their designs and spurred a wave of innovation in lockmaking. In many ways, Hobbs’ exploits were an early example of what we now call responsible disclosure—a practice where security researchers identify vulnerabilities and share their findings to improve the overall security of a system.

Hobbs and the Bug Bounty Connection

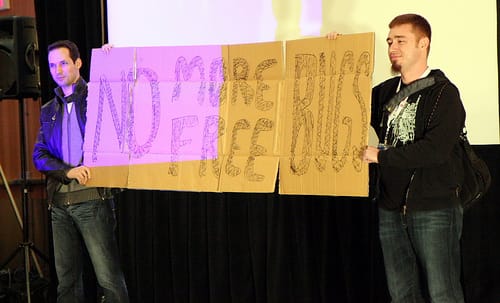

Hobbs’ story is often cited as one of the earliest examples of a bug bounty program. The reward offered by Bramah for picking their lock was essentially a challenge to the security community—a call to test the system and prove its resilience. While the term "bug bounty" wouldn’t be coined for another century and a half, the principles were the same: incentivize skilled individuals to identify weaknesses and provide feedback that can drive improvement.

The first security bug bounty that we can find ever was in the 1850s at the World Fair. A company basically put out a reward worth 50,000 US dollars in today’s currency to see if anyone could break this unbreakable lock. It was a marketing stunt—they actually didn’t think it was possible. But then this guy named Charles Hobbs came in and showed them that it was.

The parallels between Hobbs’ work and modern bug bounty programs are striking. Both rely on the breaker mindset to identify vulnerabilities, and both demonstrate the value of inviting external scrutiny to improve security. Hobbs’ legacy lives on in the hacker community, where his approach to problem-solving continues to inspire.

Lessons for Security in 2025

Hobbs’ story is more than just a historical curiosity, it’s a case study in the principles that underpin modern security practices. Here are a few key lessons we can draw from his work:

- No System is Perfect: The belief in unbreakable systems is not just naive, it’s dangerous. Security is not a destination but a journey—a continuous process of identifying and addressing vulnerabilities.

- The Value of External Perspectives: Hobbs was an outsider, and it was precisely this outsider perspective that allowed him to see what others had missed. In today’s world, this principle is embodied in bug bounty programs and vulnerability disclosure initiatives, which invite diverse perspectives to strengthen security.

- The Importance of the Breaker Mindset: As I’ve often said, “Builders build stuff, but then this breaker mindset comes in and tests all the assumptions that have been created, finds the gaps, provides feedback, and from there you can grow and improve”. Hobbs exemplified this mindset, and his work serves as a reminder of its importance.

- Transparency and Accountability: Hobbs’ exploits forced manufacturers to confront the limitations of their designs and take responsibility for improving them. This principle is just as relevant today, where transparency and accountability are critical to building trust in security systems.

Hobbs’ Enduring Legacy

Alfred Hobbs was more than just a locksmith, he was a pioneer, a disruptor, and, in many ways, the original bug bounty hunter. His work challenged the assumptions of his time and laid the groundwork for a more rigorous approach to security—a legacy that continues to influence the field today.

Hobbs’ story is a testament to the power of curiosity, creativity, and the willingness to challenge the status quo. It’s a reminder that security is not about achieving perfection but about embracing the process of continuous improvement. And it’s a call to action for all of us, whether we’re building locks, writing code, or securing systems, to adopt the breaker mindset and never stop questioning, testing, and improving.

In the end, Hobbs’ greatest contribution wasn’t just the locks he picked or the vulnerabilities he exposed, it was the mindset he embodied—a mindset that has become the foundation of modern security.

For that, we owe him a debt of gratitude.

For more reading, this Slate article provides an excellent narrative account.